#######################

6. THROWBACK THURSDAY: The entire 18th

Century; in the Colonies of Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky

HANGIN’ WITH DANIEL BOONE

and/or

HUNTING FOR SKAGGSES

Sometime around 2005, my dad and his brother

Justin (aka “Uncle Dus”) got into an informal competition as to who could

remember and write down the most old family stories, which they both proceeded

to send to me in letter-like installments. Recently, leafing through some of

these, I came upon an overlooked but intriguing PPS from Uncle Dus:

“I was typing you a page on my new computer about

your great-great-grandmother Nancy Skaggs Elkins,” he wrote, “and how she was

descended from a bunch of boys that were part of Daniel Boone’s posse of long

hunters, but I pressed the wrong button and lost the whole blame thing. I guess

it’s back to Computers For Dummies.”

Daniel Boone? Long hunters? This was too juicy a

clue not to follow up, and I soon found myself likewise online and thoroughly

tangled in the dense genealogical thicket of the Skaggses, a prolific clan that

landed on the American frontier toward the end of the 17th

century. (The name Skaggs, by the way, comes from a Norse word meaning

“bearded;” in modern Norse, it’s “skjegg.”)

|

| A longhunter re-enactor fires his long rifle during a modern-day gathering of Skaggs descendants. | |

In an article called "Be Safe and Keep Your Powder Dry," published on Facebook in 2018, one Daryl Skaggs of Scaggsville, Maryland provided the backstory:"Ire

Skaggs was born in 1580 in Londonderry, Ireland, the son of Skeggs. He had two sons

with Moira Tenny. Ire Skaggs was living in England when the Elizabeth

I’s Royal Navy roundly defeated the greatest navy in the world: the

Spanish Armada.

"William (Busel) Skaggs was born in 1600 in

Ireland, his father, Ire, was 20 and his mother, Moira, was 20 years

old. He married Mary Elizabeth Hatch and they had four children

together. He also had two sons and one daughter with Mary Hatch.

"William

Skaggs married Mary Elizabeth Hatch in Cambridge, Cambridgeshire,

England, on October 31, 1634, when he was 34 years old.William's

occupation was Ships Captain.William (Busel) Skaggs had two sons, Thomas

and Richard Skaggs."

I soon discovered that, in 1700, my

8x-great-grandpa James Skaggs (1700-1781) was born to Richard Skaggs and

his wife Mary during their sea voyage from Londonderry, Ulster, Ireland to the

British colony of Virginia. In due time, James grew up, married Rachel

Moredock (b. 1697), and sired 12 offspring, including eight rowdy boys.

All of James’s sons went a-longhunting at some

point, although the most famous of the clan were Henry, Charles, Jacob, and my

7X-Great-Grandpa, another Richard (1738-1818).

To explain the long-hunting thing, I call upon

still another Richard, better known as country/bluegrass musician Ricky Skaggs.

Ricky’s 7X great-grandfather John “Gourdhead” Skaggs (1728-c. 1770) was my

ancestor Richard’s big brother.

|

| Cousin Ricky |

John also married another of my forebears, Ruth

Elkins (and how Southern is that?), thus Ricky and I are some kind of cousins

twice over (though I’m afraid I’m not Southern enough to try to figure out

exactly how).

In his autobiography, Kentucky Traveler, Ricky

explains:

“My [Skaggs] ancestors came out of old Virginia and

migrated into the area that later became Kentucky. They were nosing around in

these mountains in the 1760s, even before Daniel Boone.

“They belonged to a group of sharpshooting

explorers called long hunters, and they went on expeditions in bands of twenty

or thirty men, sometimes for as long as two years, hunting, mapmaking, and

charting the waterways and the tributaries.

[Editor's note: Uncle Dus's son, Cousin Wayne Hill, recently noted that Richard's son, Benjamin Franklin Skaggs (1764-1863), was a boon companion of Daniel Boone's son, who went by "Daniel M. Boone." Both were also longhunters, and their names appear together on documents all over the territories they explored.]

|

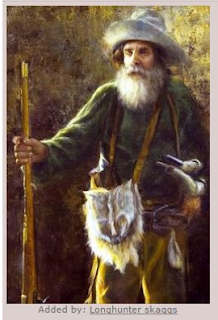

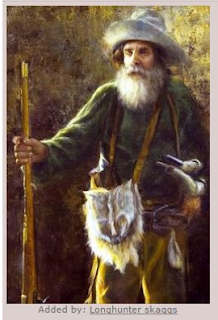

| Romanticized portrait of a long hunter. |

|

"Daniel Boone was perhaps the most famous long

hunter, and he was the one who brokered, organized and directed many of the

expeditions, which began in the 1760s. They were a phenomenon unique to the

Southern Appalachians, which were at that time primarily wilderness."

D. Boone and his very long rifle.

The long hunters’ relationship with the native

populations at that point was also highly individual; some skirmished with the

tribes, but others were adopted into, married into, or hunted and traded with

them.

|

| Much less romanticized (and probably more accurate) version. |

To the Indians, the long hunters were also known as

“Long Rifles,” being among the first to adapt the famed Kentucky Long Rifle, a major improvement in gunnery that’s considered the first

truly American firearm. This was back when a gun was deemed a necessary tool,

rather than a piece of sporting goods or a political statement.

Ricky again: “They traveled light, with just their

long rifles and the buckskins they were wearing. They kept on the move and

hunted whatever they needed to eat…. They had to leave their families behind in

Virginia, and they never knew when they’d be home. Henry Skaggs was gone so

long that his wife thought he’d been killed, and so she took another husband.

Then Henry came back and ran the fellow off. He and his wife went on to raise a

family together.”

|

| Yet

another Richard Skaggs, my 6X great-uncle. The Skaggses were that odd

commodity, Irish Baptists, and many became ministers (but not

missionaries). |

I’m happy to report that, when I went hunting with a computer, I only

got moderately lost, and found me a whole passle of lost ancestors.

|

| A Skaggs with long rifle in the Civil War era. |

|

|

By the way,

Uncle Dus never did retrieve that elusive page of Skaggs history and all those

great-grandfathers. I like to think they’re all still out there longhunting in

the farthest reaches of Cyberspace.

####################

7. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Cedar Beach, Long Island,

New York; 1948

THE LOST-AND FOUND SHELL

In 1948, I was three-going-on four, and our

family went with some friends on a rare vacation getaway to Cedar Beach, a

no-frills strip of sand on the edge of Long Island.

The beach-going conditions were less than

ideal—gray skies, high winds, high seas—but our time was limited, so blankets

were spread on the sand, people slipped in and out of sweaters as bursts of

weak sunlight alternated with chilly winds, and others waded tentatively at the

edges of the dangerous-looking roaring surf.

I was wearing a brand-new red bathing suit

with a little skirt that I imagined made me look like a ballerina. In the midst

of daydreams and propelled by a natural urge to explore, I just drifted away,

walking slowly down the near-deserted beach, examining seashells and patches of

seaweed and footprints, never even thinking about going into the water, which

looked nasty and scary.

After some time, I realized that I was alone

on the beach; I couldn’t see my family, or another soul. I didn’t panic, just

turned and walked back it what I thought was the right direction—or was it?

I reversed directions several times (I

remember passing, and re-passing the same oddly shaped patch of seaweed several

times) and just kept walking, confident that I could find my way back. In the

midst of my wanderings, I found something pretty in the receding path of a

wave, picked it up and hung onto it tightly.

|

| Cedar Beach |

Suddenly, I heard a shout, and saw a line of

strangers, four men and a woman dressed in blue bathing suits with badges sewn

on them, running toward me. Without a word, the woman swooped me up into her

arms and they all turned and ran back in the direction from which they’d come.

I was puzzled, but not really alarmed by this.

The lifeguards delivered me back to my

frantic parents, who were certain that I’d drowned in the dangerous surf. I was

hugged, fussed over, given chocolate milk, fed my first hot dog with relish,

and proudly displayed my newfound treasure, a perfectly intact bleached-white

spiral shell, which to me was the most interesting part of the whole episode.

That shell was kept on view in my parents’

house for years, inscribed in pencil was my name, and the words: “Cedar Beach

L.I. N.Y. 1948.”

Whenever the incident was recalled, my parents would get a

strange bleak look in their eyes and say softly “We thought we’d lost you.”

They loved me, and I have a shell that always

reminds me of that.

####################

8. THROWBACK THURSDAY: San Francisco,

California, and Environs; 1968-70

RULES OF THUMB; THE SINGLE GIRL'S GUIDE TO PRACTICAL HITCHHIKING

In the last years of the San

Francisco 1960s, I (and many other free-spirited contemporaries) hitchhiked

regularly.

For a year or so, I regularly

thumbed my way across the Golden Gate Bridge to a part-time job in Sausalito.

Such was the relative innocence of those times that rides were easy to come by,

and those offering them were (mostly) benign.

|

| 1974 roadside photo by Roger Steffens |

In May of 1970, working in San

Francisco (and having pretty much retired my thumb as a ride source), I put my

on-the-road experience to use in an article for Earth Times, a Rolling Stone

spinoff that was one of publisher Jann Wenner’s few miscalculations (this one

about overestimating the level of public interest in what was then known as

“ecology”).

The quirky little hitchhiking story

was quite well received; It was not only quoted (in a volume of hip aphorisms),

but anthologized (in a collection of writings about the emerging

counterculture), and even plagiarized.

This last indignity was perpetrated

by a writer for the New York Times, no less, in a December, 1970 article on

hitchhiking that featured an oddly imitative photo. His “Arts & Leisure”

story blatantly lifted sections of my text and repackaged them as quotes

attributed only to anonymous hitchhiking “girls,” with no mention of their

actual source.

(And, in case you’re wondering, I

sent highlighted copies of both articles to the Times’ legal department, which

ignored them, probably hoping I’d just go away, which I did, having more

intelligent things to do than tangle with New York lawyers and a 119-year-old

journalistic institution.)

People who read the Earth Times

article, with its advice covering a wide (and occasionally bizarre) range of

hitchhiking situations, were wont to ask me: “What was your strangest

experience?”

There were many that qualified as

odd (a sober carful of zen monks; sharing a back seat with a (caged) boa

constrictor; riding with a crew of very stoned guys in drag on their way to

entertain at a party); and even wild (clinging with four other thumbers to the

roof rack of a psychedelicized VW van as it careened crazily along the winding

road to Stinson Beach), but this one sticks in my mind.

I’d gotten a ride from an ordinary

and straight-looking guy in a late-model sedan. We were making fellow-traveler

chit-chat when he said, maybe a little too casually: “Those are nice boots

you’re wearing.” I thanked him.

“Are you wearing socks under them?”

he inquired.

“Umm, yes.” A little silence.

“What color are they?”

“My socks? They’re brown. Nylon.”

(The dregs of my sock collection; I was at the end of a laundry cycle.)

More silence. “Can I buy them from

you?”

“Nope, sorry, not for sale,” I said

lightly, wondering at the same time where this was going.

“Five dollars?”

“No.”

“Ten?”

“No!”

He got up to twenty before I said:

“Look, I am NOT selling you my socks. Can I please get out at the next corner?”

He meekly obliged. As I climbed out,

he said mildly “I don’t care for the brown ones that much,” and drove off into

the Sunset District.

Afterwards I wondered about the

psychology involved. Was it a clever way to get a look at my feet? Did he sniff

the socks or use them in strange personal rituals? Was it just me, or did he

regularly cruise for socks? Guess I’ll never know.

And then there was the Italian guy I

had to hit over the head with my clog. But that’s another story.

#######################

9. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Leicestershire and London, England, 17th and 18th Centuries

WHAT MY 7X GREAT-UNCLE CHARLES AND

HIS GOOD FRIEND GEORGE GOT UP TO IN THE SUMMERHOUSE

Once upon a time, long before my 8X

great-grandfather William Jennings arrived in the Virginia Colony in 1690 as a

captain in the British army, my paternal grandmother's ancestors had become, to

put it politely, stinking rich.

The family fortune, dating from the

17th century, was derived from the iron trade, and G-G-G-G-G-G-G-G-Granddad

William was the 10th child of 13 sired by one Sir Humphrey Jennings (who was

never actually knighted, but since he owned over half of Warwickshire, he could

call himself whatever he damn pleased).

Although William made out OK in Sir

Humphrey’s will, it was his oldest brother, Charles who (as was usual in those

times) got most of the land and loot, including a fine country house called

Gopsall Hall in northwest Leicestershire.

In the fullness of time, the

now-very-wealthy Charles Jennens (the spelling he preferred) and his wife Mary

Cary Jennens had a son, also called Charles.

Along with having inherited the

family flair for making and keeping money, the younger Charles was a bachelor

gentleman scholar who loved to dress well (check out all that elegantly frogged

green velvet), and hang with artists and musicians.

|

| Charles |

He also picked up a bit of a

reputation as a writer and librettist, not to mention the nickname “Soleyman

the Magnificent,” for his expensive lifestyle at Gopsall Hall, which he had

rebuilt in grand style in the 1750s.

|

| Gopsall Hall |

Among other extravagances, Charles

Jennings commissioned a fancy summerhouse on the grounds of the Hall, and had a

full-sized pipe organ installed in it for the exclusive use of his good friend

George, another confirmed bachelor who liked to dress well.

|

| George |

One day in July of 1741, Charles

gave George a new libretto for an oratorio.

"Thanks," said

George," This looks good; I'll put some music to it."

The resulting

collaboration debuted at an Easter charity event in Dublin on April 13th, 1742. Although its initial reception was

so-so, this piece generated some good buzz (especially that catchy chorus), and

has survived to this day.

Gopsall Hall (now Gopsall Park)

currently belongs to the British Crown.

The portraits of Charles and George, both by Thomas Hudson,

belong to the Handel House Collections Trust.

Their "Messiah" belongs to

the ages.

#########################

THROWBACK THURSDAY: San Francisco

Folk Music Club (SFFMC) Headquarters, 885 Clayton St., San Francisco,

California; c. 1970-78

10. U. UTAH PHILLIPS; A FIGMENT OF HIS OWN IMAGINATION

|

| U. Utah in the 1970s |

As I’ve written here before,

musician’s musician and champion networker Rosalie Sorrels was wont to show up

at 885 Clayton St. with all manner of interesting persons in tow. Over time,

she brought us music legends, singers, instrumentalists, songwriters, poets,

storytellers, and political activists.

|

| Rosalie and Bruce, on the road. |

Then one day, she showed up with

someone who fit all of these categories at once, and many more.

This was Bruce Duncan Phillips, then

just beginning to showcase an ingenious “invented personality” that would

become, over the next 38 years, known and beloved as “U. Utah Phillips, The

Golden Voice of the Great Southwest.”

|

| Portrait of U. Utah by David Shetterly |

In a 1972 Rolling Stone article, I

wrote of U. Utah (the name was a takeoff on country musician T. Texas Tyler):

“He’s a conspicuous enigma, a blend of Mark Twain and Will Rogers, with a touch

of P.T. Barnum and more than a hint of Huck Finn.”

In his 2008 obituary, New York Times

writer Jon Pareles described Bruce/Utah to a T:

“An instinctively independent

guitar-slinger and self-described anarchist with an affinity for history and a

trove of one-liners, Mr. Phillips was a regular on the folk circuit from 1969

into the 21st century. 'It is better to be likable than to be talented,' he

often said.

|

| Bruce eyes up Carol Mayfield at a San Francisco Folk Music Club house concert. (Photo by Roger Steffens) |

“His sets were monologues that

interspersed anecdotes, political jabs and wry observations with songs — some

traditional, some from the labor movement, and some he had written…

“His songs were recorded by Emmylou

Harris, Tom Waits, Joan Baez, Waylon Jennings, and Ani DiFranco, who signed him

to her label, Righteous Babe, and produced two albums for him in the 1990s [one

of which was nominated for a Grammy Award]. Mr. Phillips sang about workers,

historical events, the West and his great love, trains.”

|

| Album cover with Ani DiFranco. |

Back in 1972, Bruce told me that he

decided to create U. Utah after being made unwelcome in his home state for

organizing migrant laborers there into a significant political force. Later,

onstage, he would claim it was because of a sheep-assault rap (“Out there it’s

a capital crime—capital experience, too!”)

His approach to becoming an

entertainer was typical of the man; he spent months studying voice production,

delivery and comic timing. He watched films of comedy greats, and listened for

hours to old records and tapes of radio comedy and vaudeville routines.

To all that research, he could add a

wealth of experience gained in preceding years (he was 38 when I wrote the RS

article). On his resumé:

College dropout; Korean War vet;

railroad bum; assistant to an Episcopal minister to the Navajo; accomplished

fencer; plasterer/finisher; founder of both the Utah Science-fiction League and

the International Rocket Society; professor of poetry; high-school physics

instructor; printer and lithographer; warehouseman; camera and tape-machine

repairman; Army radar/technological/demolitions expert; Archivist for the state

of Utah (seven years); head of the Utah State Records-Management Program;

co-founder of the Poor People’s Party (which became Utah’s Peace & Freedom

Party); IWW agitator and organizer; husband (three times); and father (two

sons).

|

| Album cover: Bruce and Rosalie |

In time, legend would add a few more

categories: Old Wrangler; duck rancher; notorious sheep-diddler; hobo;

preacher; philosopher; and, above all, superb entertainer.

As years went by, with Bruce a

fairly frequent houseguest at 885 Clayton, we got to observe his gradual

transformation into living and believing the part of U. Utah. There were

certain elements common to both personalities—a deep integrity; a quick and

brilliant wit; a passion for justice and sympathy for the underdog; a love of

history; a wildly poetic way with words; a profound sense of the ridiculous.

Fortunately, both Bruce and Utah

were excellent company, and stories, one-liners and aphorisms tried out at the

breakfast table were likely to find their way into his act.

“Growing up, I was an imaginary

playmate.”

“Nothing ever gets old anymore;

first it’s new, and then it’s junk.”

(Of his lady friend) “We’re

compadres; that’s two people riding in the same direction on different horses.”

It was Bruce who first dubbed Faith

Petric (885 Clayton landlady and SFFMC prime mover) “The Fort Knox of Folk

Music,” for her enormous knowledge of and memory for even the most obscure of

songs. The two of them quickly became cronies and often appeared together

onstage.

|

| Bruce and Faith perform together in the 2000s. |

When I found the first YouTube clip

below, I was charmed to find that a shaggy-dog story I’d once told Bruce had

been adapted into U. Utah’s act. (He and I were probably the only two people I

ever knew to find it pants-wettingly hilarious.)

I treasure one private glimpse of

the guy; one morning, as I came downstairs at 885 Clayton, I heard a kind of

rumbling repetitive hum, somewhat like a musical bumblebee caught in a jar. I

peeked into the living room, and there was Bruce, memorably attired in a long

plaid flannel nightshirt, Mary-Jane style Chinese slippers worn over white

socks, and a multicolored beanie topped with a propeller.

He held a bottle of bubble stuff in

one hand, its wand in the other, softly conducting his own voice with a cloud

of bubbles as he concocted another U. Utah Phillips standard.

I couldn't help but smile—It was

classic Bruce; a man refreshingly deep into his creative process and completely

at peace with his own eccentricities.

There will never be anyone else like

him.

11. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Peterkin Hill, South

Woodstock, Vermont; Thanksgiving 2002

A CHIP OFF THE OLD GRANDDAD

This act of artistic/electric whimsy

was perpetrated on a pumpkin during the celebration of Thanksgiving 2002. My

dad, then 89 years old, was spending the holiday in Vermont at the home of my

brother David, his wife Susan, and their ten-year-old daughter Morgan.

I have no idea whose idea it was,

but my dad and Morgan being two of a kind, they put their heads together and

produced this unprecedented melding of low tech and vegetable matter to light

up the holiday décor.

Someone, probably my sister Sue,

recorded the event, which was probably a first in the annals of Thanksgiving

history.

Morgan, who went on to become head of the print department for the

New York fashion house of Diane Von Furstenburg, has many fond memories of her

“Papa;” this is probably one of them.

########################

12. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Graton, California, c. 2005

A TOTEMIC DICHOTOMY

Some time back, I was talking with

an artist friend who’s into totems. She asked me what animals I really related

to.

“Bunnies and owls,” I replied.

“Whoa,” she said, “That’s quite a

dichotomy. Do you use them in your artwork?”

“Actually, yes,” I said, “I recently

did a collage that used both of them.”

“As totems?”

“Not exactly.”

“As Winnie-the-Pooh cartoony

characters?”

“No, as real animals.”

“Interacting?”

“Yep.”

“How did you do that without it

turning into a predator/prey scenario?”

Here's how:

##################

13. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Occidental,

California; Early 2000s

HIS HONOR THE PECKER, or WHY DID THE CHICKEN…?

Once upon a time, at the start of

the new millennium in the tiny village of Occidental, a truck laden with cages

full of live chickens paused at the hamlet’s single stop sign, on

its way to who-knows-where.

What happened then was witnessed by

“Ranger Rick” Kaufman, Occidental’s self-appointed street-sweeper and

character-at-large.

As Rick looked on, a sizeable golden rooster wriggled his

way out of a cage, perched for a moment on the tailgate of the truck, and

fluttered down to the surface of Main Street.

|

| Ranger Rick |

According to the Ranger, the

handsome bird (as the truck rolled on without him) fluffed his feathers back

into place, straightened up to his full height, crowed lustily, and strutted

across Main Street to assess his surroundings

Thus began the tenure of “Mr.

Pecker” (as the charismatic fowl soon became known) as Mayor of Occidental,

which, as an unincorporated village, had none at the time.

Mr. P. was a bird of innate dignity,

and patrolled the streets with an air of gravity and high responsibility.

Occidental residents and shopkeepers became used to the sight of him strolling

down the sidewalk on his daily patrol, surveying the village’s activities,

occasionally stopping to partake of offerings of cracked corn and grain that

began to appear outside of shops and restaurants.

When tourists (a major part of the local economy) exclaimed at the sight of him, they were told, in no

uncertain terms: “That’s our Mayor.”

Eventually someone thought he looked

a bit lonely and imported a sweet little brown hen, immediately dubbed “Mrs.

Pecker.” Their affectionate union produced a flock of little Peckers.

|

| Mrs. Pecker |

Unfortunately, since Occidental is

surrounded by redwood forest harboring all kinds of chicken-hungry critters,

the little ones quickly disappeared (or perhaps were chicknapped by someone

wanting to start a flock). Mrs. P. likewise disappeared soon thereafter, and

the Mayor was left a lonely widower.

|

| Mr. and Mrs. P. nap in a shop entrance on a rainy day. |

His Honor himself seemed to be a

master at evading predators, roosting in trees at night, and with fluffed

feathers and a ferocious glare (but no violence), intimidating dogs and small

children who attempted to catch him. His tenure as Mayor was to last for

several years of tranquility and prosperity.

Then, as suddenly as he had arrived,

he disappeared. Ranger Rick, his confidant and sometime drinking buddy,

asserted that he had gone to Sacramento to see how they did government in the

big city; he was also, Rick said, considering a run for governor.

Why did the chicken cross the road?

To answer the siren call of public office, of course.

|

| Checking out road conditions. |

|

|

#######################

14. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Interlocken Center

for Experiential Education; Hillsboro, New Hampshire, Late 1970s-1990s

THE INTERLOCKEN EFFECT; SEEING BEYOND THE OBVIOUS.

Of the many remarkable people I met

at Interlocken, one of the most deserving of that adjective was Sarah Gregory

Smith.

Lovable, witty, whip-smart, and

kind, Sarah was a fine musician (guitar, string bass and woodwinds) and singer,

and a crackerjack contradance caller. In addition to teaching music and dance,

she managed the camp’s mini-farm program, taught baking, and helped inspire and

organize Interlocken’s annual folk festival.

She also taught a class that many

Interlocken alumni will never forget; it was called “On Blindness.” Sarah, who

had become completely blind as an adult as a result of complications of

diabetes, had, typically for her, turned a physical limitation into a gift.

|

| Sarah teaches a student in "On Blindness." |

Her

gentle mission was to teach people at Interlocken about blindness; how to

relate positively to blind people, and about how to interact positively and

helpfully with the vision-impaired.

For many Interlocken students and

staff members, this was their first opportunity to ask questions and receive

honest answers about blindness; to learn the many ways Sarah knew of

negotiating a world without sight; and to understand how to offer assistance to

the blind (and how and when not to).

Sarah seemed fearless; she swam,

hiked, camped, sailed, tackled the ropes course and ran in the camp’s annual

footrace, the “Andy Upton Classic.” In my first summer at Interlocken, I ran

the race as one of Sarah’s “guides,” one of us on either side of her as she

navigated to the sound of our footsteps.

Whenever you saw Sarah at the camp,

she was likely to be surrounded by a gaggle of kids vying to walk with her,

talk with her, sit with her at meals and meetings. If this got a bit wearisome,

she never let on.

In all these endeavors, Sarah had as

cohort and companion her husband, the genially unflappable T. William “Smitty”

Smith, himself a wonderful musician and storyteller who also taught

carpentry/woodworking/construction, and organized the camp’s weekly sings.

|

| Sarah and Smitty at Interlocken in the 1980s |

Smitty could turn his hand to all kinds

of programming and administrative tasks by day, and by night electrify an

audience of kids with his banjo-accompanied recounting of a Georgia Sea Islands

tale concerning Jack and Mary, who, lost in the woods, fall into the hands of a

wicked old woman, and are rescued by the three titular dogs of the piece—Barney

McCabe, Doodley-Doo and Soo-Boy.

For over a decade, Sarah and Smitty

were a beloved Interlocken institution, but Sarah’s beginnings were, if

anything, a bit shaky, as she related in a 1994 interview (which was also a

classic example of the “Interlocken effect”).

“In the winter of 1978, Smitty and I

had just gotten married, and I was now totally blind. I had lost my teaching

job, and although I was very happy with Smitty, I basically thought my life had

come to a standstill. I wasn’t going to be able to teach or do any of the other

things I loved to do—it’s hard to describe it, but I definitely felt

undesirable as a working person. I was blind, and I was not really trained in

mobility, and it was kind of a strange and flat time in my life.

“So one day the phone rang, and it

was [Interlocken Co-Director] Richard Herman, whom I didn’t know all that well,

and he said, in his usual Richard way, after not too much preamble, ‘We’re

building a dance pavilion, and we really want to get the music and dance

programs up and going again, and we’re looking for a musician and dance-caller

team, and we’d like you and Smitty to come and work here.

“I was completely stunned, and all I

could come out with was my now-famous question: ‘Richard, do you know I’m blind?’—I thought somehow he had missed that fact. And he said ‘Yeah. So?’ And

I was still stunned; I said ‘And you want me to come and teach dance?’

|

| Amey Win (r.) guides Samantha McGuire in an "On Blindness" class. |

"I was full of self-doubts, and

thinking, ‘How could I possibly do this? I can’t even find my way down my own

driveway, and he wants me to come and teach dancing for kids?’It was just sort

of like ice-blocks shifting against each other.

“I said, ‘Well, I guess we could

talk about it,’ but in my mind it was more like: ‘Well, if you think this is a

good idea, I guess we could talk about it, but I think you’re missing a few

things.’ Because my attitude about blindness at that time was when you’re

blind, you’re dead; your life is over.

“The long and short of it is that we

came for the summer of 1979. I remember sitting with Richard and [Co-Director]

Susan [Herman] at dinner, and trying to get an idea from them about what they

wanted us to do. I went from thinking I could do nothing to—Susan would say

something like ‘Well, we have a farm,’ and I would say, ‘Oh, I know all about

farm animals; I could do that,’ or ‘Oh yeah, I could bake bread.’

“It was a kind of never-never-land

for me. We came that year, and it was like ‘Fantasia;’ it was a miracle. For

one thing, everybody at Interlocken accepted me, much more than I accepted

myself.’”

|

| Sarah and Smitty post-Interlocken. (Photo by Deborah Schneider) |

Sunday Morning Meetings were another

beloved tradition at Interlocken. These were mostly silent outdoor gatherings,

with individuals standing up, when so moved, to share a thought, a piece of music,

a poem or journal entry. Each meeting had a theme, and on one particular Sunday

I remember, the theme was “Handicaps.”

Students and staff members got up

one by one, and shared handicaps ranging from asthma to ADD, extreme shyness to

dyslexia, hearing impairment to the inability to hit a softball. Then Sarah

stood up. The silence was complete. As the others had done, she started out: ”I

have a handicap.” You could have heard a pine needle drop.

Then she said: “I

have a really hard time memorizing music.”

Like Richard Herman and Sarah

herself, sometimes you have to look beyond the obvious.

|

| Smitty and Sarah with friend Sandy Davis (c.). Sarah passed away in 2019. | |

|

###################

15. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Renaissance Pleasure

Faire; Los Angeles Herald-Examiner; March 16, 1973

THINGS FOUND IN OLD ENVELOPES #7;

MORE TICKLEBOTTOM BY REQUEST

The clipping below was sent to me by

the late Jim Kahlo, who for many years portrayed the original Renaissance

Pleasure Faire’s adorable skirt-chasing guildmaster, one J. Pluckem

Ticklebottom.

The photo captures the single Faire

season that I played the Mistress of Misrule (a pleasant naughty-bawdy change

from virginal May queens and demure harvest maids) on the way to becoming

Mistress of Revels.

In the early days of the event, Jim

and I, when not occupied with onstage duties, would frequently stroll about the

Faire arm-in-arm. This was partly because the disparity in our ages and Jim’s

snowy hair and aquiline features created a wonderful photo-op for visitors, but

also because his advancing arthritis made it difficult for him to tread uneven

outdoor surfaces safely on his own.

Jim was a true gentleman with the

heart of a scalawag. His informal penciled captions on top of the clipping were

typical:

“Ticklebottom’s Love Upstaged By a

Gay Hobbyhorse; or Love Goddess Watches to See That Centaur Keeps a Firm Hold

on Himself.”

That Centaur was former Mouseketeer

Dennis Day, a brilliant and wildly unpredictable clown, dancer and comedian who

enlivened Pleasure Faires and Dickens Christmas Fairs for many years. (His music-hall

rendition of “I’m One of the Queens of England, But I Can’t Remember Which” was

not to be missed.) Dennis is riding on (actually in)

one of the ever-increasing number of elaborate hobbyhorses that added visual

pizazz to any parade or procession.

|

| The late Dennis Day, horsing around. |

Jim and I also teamed up at the

early Dickens Christmas Fairs, he as a deceptively saintly-looking Father

Christmas, and I as his brigadier general. He also often popped onto the scene

as Father Time for the post-Christmas weekend.

I’m happy to say that the Dickens

Fair, founded in 1970, is still going great guns and occupying ever-increasing

acreage at San Francisco’s Cow Palace between Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Without, however, Dennis, me or Jim, all kept away by extenuating circumstances

of time, distance and/or mortality.

#####################

16. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Somewhere in

Pennsylvania, 1979

DR. ORNISH MAKES A HOUSE CALL

I have a warm spot in my heart for

Dr. Dean Ornish, but not because he’s a superdoc diet/lifestyle guru, author,

columnist, lecturer, and advisor to presidents.

My appreciation goes back to 1979,

at which time Dean, not long out of medical school, was holed up in the new

York City Public Library, working on the manuscript that would become his first

ground-breaking book, Stress, Diet, and Your Heart.

At that time, with the best of

intentions, I had gotten myself into a live/work situation in a conservative

part of the country where I was surrounded by salt-of-the-earth people whose

politics were somewhere to the right of John Wayne’s, and who had strong

negative opinions of “all that California hippie crap.”

In other words, my previous life in

1970s Northern California.

I quickly learned to avoid political

discussion, keep my head down, and refrain from mentioning incendiary topics

like organic food, recycling, gender equality, renewable energy, alternative

forms of medicine, etc., lest I be faced with various levels of opposition and

derision.

There was no Internet then, and I

had no reliable source of transportation, and minimal access to public radio

/television/books on the above subjects. It was little wonder that I began to

feel isolated, and as if all my values really were that strange, and maybe a

little —crazy?

In desperation one day, after a

particularly daunting encounter, I called my friend Karen Thorsen in New York

City. Karen was then an editor at LIFE magazine, and had a wide circle of

interesting acquaintances. She listened to my tale of lonely self-doubt, and

said: “There’s somebody I think you should talk to. Would you mind if I gave

him your number?”

A few hours later, I received a call

from a soft-spoken guy named Dean, with whom I conversed for a few minutes

about my situation. “You know,” he said, “I think we need to talk in person.

Would you mind if I came to see you?”

Somewhat nonplussed, I gave him

directions, and the next day he arrived, a homely, lanky guy with thoughtful

eyes and an almost preternaturally reassuring manner. He immediately presented

me with a hardcover copy of Marilyn Ferguson’s The Aquarian Conspiracy, and

suggested we take a walk.

We went to a nearby wooded area with

a stream running through it, and each chose a rock to sit on. Then, with great

kindness, he gently convinced me that the world was indeed changing in the

direction of the values I embraced.

He told me about his upcoming (and

ultimately wildly successful) crusade, based on the science behind his clinical

studies, to show that heart disease could actually be reversed without drugs or

surgery, using a combination of diet, exercise, meditation and social support.

He also clued me in on other hopeful developments in science, medicine,

computer technology, energy, and agriculture.

Dean listened as well as he spoke,

and after our exchange of ideas, which lasted well over two hours, I felt

refreshed, inspired and mentally fortified (though I did decide to return to

California not long afterward).

|

| (from a 1994 interview

I did with Dean) |

Although we kept in touch, our paths

occasionally crossing, I’ve mostly just enjoyed keeping track of his ever-expanding

career, knowing that inside that Superdoc lab coat is a guy who once thought

nothing of breaking into his valuable work time and making a four-hour round

trip solely for the purpose of comforting and reassuring a perfect stranger who

was temporarily lost in strange surroundings.

OK, I’ve got to say it: The man has

heart.

#####################

17. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Wilson Borough Area Joint

Junior-Senior High School Junior Prom; Wilson Borough, Pennsylvania, 1961

GOING FORMAL

Back in 1961, when one went “to the

prom” instead of “to Prom,” it was a whole different, and much simpler, world at

Wilson High School.

No staying out all night and getting

wasted. No rented limos, hotel suites, expensive after-prom parties, or

celebrity entertainment (we were lucky if we got a live third-string Lester

Lanin Orchestra). No couture dresses or designer shoes (“dyed-to-match” was,

however, a big deal).

Some girls, those from wealthier

families, might spend as much as $50 for a prom dress. The fashion then was for

strapless confections with enormous poufy multi-layered net skirts, clouds of

petticoats, and tight itchy bodices.

Since I wasn’t a fan of overstuffed

discomfort, I was surprised and delighted when I found this simple little white

cotton eyelet number with pale-blue sash—$11 at a local teen shop.

My escort was a budding jazz

saxophonist named Terry Siegel—he actually turned pro after college—for whose

sake I endured not one, but two, mind- and butt-numbing Maynard Ferguson

concerts, utterly wasted on me. No wonder we broke up.

Terry’s rakish eyepatch, by the way,

was covering a minor injury involving, as I recall, a parakeet and a vacuum

cleaner (don’t ask).

Those were, indeed, the days (and

let’s also just not talk about that hairdo).

###################

16. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Scotland, Vermont, San

Francisco, Carnegie Hall, and Various Other Locations; 1940s-Present

NORMAN KENNEDY: A SCOT LIKE NO OTHER

The first time that I encountered the guy, he

had an entire folk-festival workshop crowd on its feet, bouncing and

step-dancing and toe-tapping, simply by singing to them.

No instruments, no percussion, just a nearly

lost Celtic art called “mouth-music”— Gaelic nonsense songs, sung in dance

rhythm and dating from a time when the Scottish Kirk had banned dancing as the

work of the devil, and all instruments of jollity as the same.

He sat almost nonchalantly onstage, red-gold

hair gleaming, a study in vocal dexterity, pinpoint rhythm, and effortless

charisma.

“Who is that?” I asked the toe-tapper

standing next to me.

“That” he said, “is Norman Kennedy. Uncanny,

isn’t he?

It was the early 1970s, and Norman, I

learned, was just coming off a six-year stint as Master Weaver at the Colonial

Village in Williamsburg, VA. As a performer, he could (and still can) hold any

audience spellbound with his seamless flow of songs, stories, folklore, and

humor, often flavored with a hint of bawdy, and a dash of—yes—uncanny, which he

comes by naturally.

Born in Aberdeen, to a seagoing and

shipbuilding family that traces its Scottish origins back to 13th-century

Danish sea rovers, he spent most of his childhood hanging out with old folks,

including his three great-grandfathers.

“The old ones, they had all the secrets

and stories and traditions, and the weaving and spinning and carving, and half

of them were psychic besides. Much more interesting than kids my age.”

He became known as a budding collector of

songs and stories, and remembers that, at the uproarious Scottish end-of-year

celebration known as Hogmanay, "The old ladies who’d been having a wee

tipple would crowd me into a corner and insist on teachin’ me rude songs till

my ears turned as red as my hair.” (These experiences were later to make him the

life and soul of every folk-festival “Bawdy Songs” workshop.)

He left school at 16 and, after apprenticing

informally in the weaving arts, headed for the Outer Hebrides, harvesting more

songs, stories, craft secrets, and folklore, communing with standing stones on

Midsummer Nights, and consorting with a shy people for whom second sight was

second nature.

Returning to Aberdeen, he appeased his family

by taking a job in the civil service, but also built a still and his own looms,

wove and spun and tended and sheared sheep, all the time singing for friends

and family and occasionally for pass-the-hats in the local pubs.

This all changed in 1965, when he was

“discovered” by Mike Seeger (musician/musicologist brother of Pete), who

invited him to perform at the Newport Folk Festival. This led to his first

record album and an ongoing mutual love affair with the US, especially Vermont,

where he started a crafts cooperative and weaving school, and now lives.

So, did I say uncanny? Here’s an anecdote or

two: I once overheard the following conversation, when a friend asked Norman if

he’d heard from his father lately. “Och, he’s nae speakin’ to me now.” “Why

not?” "Oh, the same old thing; I wouldnae put a curse on the neighbors for him.”

On another occasion, a young woman friend

asked him to read her tea leaves. Ever obliging, he glanced into the cup, and

exclaimed “I see a cradle; are ye expectin’?” “No!” she replied emphatically. A

subsequent pregnancy test proved that, actually, she was.

Then there was the time, after hours at the

Mariposa Folk festival in Toronto, when, as part of a circle of master

storytellers (English, Scottish, Irish, Jewish, Abenaki Indian) Norman reduced

an entire roomful of listeners to pants-wetting sleeplessness with a tale that

began something like this:

“I was on the way home one evenin’, and I saw

old Mrs. Murray comin’ towards me, walkin’ doon the road in her Sunday dress.

Which was peculiar, because she’d died and was buried in it two weeks ago. Then

I smelt a fearsome stench, and I couldnae but happen to notice that she was

rotten, the bits of skin fallin’ off of her onto the ground, and she hummin’ a

wee hymn tune, the one we sang at her funeral.” It got scarier.

It was also in Toronto, at a week-long crafts

and folkways exhibition at the Ontario Science Center, that Norman got to

hobnob with royalty. One day, the entire hall complex was shut down, visitors

were escorted out, and performers and other functionaries were herded up to a

high balcony overlooking the exhibit hall; the craftspeople had been told to

stay and go about their business.

Then, of all things, in came Queen Elizabeth

the Queen Mother of England (and Canada), elegant in a lime-green ensemble with

sprays of diamonds, flanked by two gigantic kilted and sword-bearing Scots Guardsmen.

She made a beeline for Norman, as he sat weaving, and we could see the two of

them engaged in lively conversation for several minutes. She smiled and gave

him her hand, over which he bowed with the grace of a consummate courtier.

|

| With clean diamonds. |

“What were you talking about?” we asked

later. He was hilarious on the subject of the guardsmen, with their dour faces

and their swords half-drawn: (“What the devil did they think I was goin’ to do?

Shove a shuttle up her nose?”)

They had, he said, talked about weaving (she

was an admirer of his work), and about “waulking” (the charming traditional

Scots method of texturizing newly woven wool by soaking it in human urine,

laying it out on a table, gathering around, and pounding it into submission

with fists, often to the tune of chant-like “waulking songs).”

“She’s a lovely wee lady,” observed Norman,

“but her diamonds were dirty. I’ve a grand recipe for cleanin’ them, but I

didnae like to mention it.”

The shoe was sort of on the other foot one

day in the late 1970s when I had the opportunity to hang out with Norman in San

Francisco, where he was appearing at the Great American Music Hall. He wanted

to visit a number of yarn and weaving-supply shops, and needed a friendly

native guide.

I soon discovered that the effect of Norman

Kennedy walking into a weaving shop was kind of like that of the Queen Mum at

the Science Center. Not only did most of the owners and sellers recognize him

on sight or by name, they practically genuflected.

Norman was looking especially fine that day,

dressed in perfectly faded jeans and a knitted pullover (he’d whipped it up

himself) that would have sold for megabucks in a Nieman-Marcus catalog.

Slim, trim, copper-maned, and lambent with charisma, he

requested a side trip to North Beach Leather, a shop full of expensive and

imaginative styles often seen on rock stars of the day. He charmed the

oh-so-hip young salespersons from the word go, and went to the dressing room to

try on a few garments.

“Who IS he?” they asked in whispers, “I know

he’s somebody I should recognize, but…” The temptation was irresistible. “He

prefers being incognito,” I replied, a little loftily. ”No autographs, please.”

He paid cash for his purchase, and as we left, I saw the entire staff gathered

at the door of the shop, looking after us, still speculating on his identity.

|

| No autographs, please. |

Norman closed his weaving school in 1995, and

“retired” to a life of weaving and spinning his own designs, presenting workshops in his

impressive roster of crafts and skills, and performing. In 2003, he was awarded

a Heritage Fellowship from the National endowment for the Arts.

Not that long ago, he was invited by

brilliant traditional fiddler Natalie McMaster (whom he’d known since she was

14) to appear as her opening act for a concert at Carnegie Hall.

A week or so

before the event, he was contacted by one of the venue’s stage managers,

requesting a printed schedule of every song and story he intended to present,

with the exact running time for each. Norman patiently explained that he didn’t

work that way, and when the fellow became adamant, suggested they find someone

else.

|

| Natalie McMaster |

With Ms. McMaster's intervention, Norman got

his way. On the night, he said to the somewhat nervous stage manager. “Right!

How long have I got? 50 minutes?” He proceeded to go out into the spotlight and

spin a delightful skein of songs and stories seemingly off-the-cuff, enchanting

the audience and warming them up but good.

As he came offstage to a roar of applause, he

encountered the stage manager, who was clutching his timepiece and looking

slightly stunned.

“How long was I on, then?” asked Norman (he

wasn’t wearing a watch). The fellow just stared at him, then admitted,

re-checking the time: “50 minutes, exactly.”

“Laddie,” said Norman, kindly, "I’ve

been doin’ this since before ye were a twinkle in yer father’s eye,” and

off he walked to the dressing rooms, humming to himself.

As I said, Uncanny.

########################

18. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Cape Cod, Massachusetts,

c. 1947

SITTING PRETTY

My cousin Robert Ralph Arnts, going through old family photos, unearthed this sunny snapshot

of three generations of bathing beauties. My aunt Jean Arnts Wixon Fleming is

on the left, next to my grandmother Clara Arnts and my mother Barbara Arnts

Hill. My big sister Susan and I, in matching red two-piecers, are happily

ensconced on laps, all of us just happy to be hanging out in our own little

slice of summer.

####################

19. THROWBACK THURSDAY: San Francisco, California,

1963-1970, and worldwide; 1935 to 2011

THE OWSLEY EFFECT: YOU JUST CAN’T MAKE THIS STUFF UP, VOL. IV

To his family, he was Augustus Owsley Stanley

III, namesake son of a prominent US government attorney and grandson of a

congressman and Governor of Kentucky.

To the Grateful Dead and their employees and

adherents, he was “Bear,” their brilliant and inventive sound engineer and

house alchemist.

To the 1960s counterculture at large, he was

simply Owsley—one name, like Cher, or Voldemort—outlaw folk-hero and

maker/purveyor of the finest and purest LSD available.

Born in 1935, Owsley as a youth was a study

in ongoing embarrassment to his distinguished family. Sent to military school,

he was expelled for getting his entire class drunk. Committed to a psychiatric

institution, he encountered the poet Ezra Pound and learned how to rebel more

subtly.

A natural polymath and autodidact, he spent

two years at the University of Virginia studying engineering, dropped out, and

joined the Air Force, where he specialized in rocketry. On his discharge, he

took up, of all things, ballet, and became a proficient enough dancer to make a

living at it.

In the early 1960s, he gravitated to UC

Berkeley, where he quickly became enamored of the emerging counterculture,

dropped acid, and emerged to dominate the Grateful Dead’s sound crew,

constructing and adapting equipment as the band’s distinctive resonance took

shape. He also recorded most of their concerts as feedback for improvement.

Owsley made his first batch of LSD in 1963,

when it was perfectly legal (and would be until October of 1966). He used the

purest ingredients obtainable from legitimate labs, designed special glassware

for the process, and experimented with blends like “White Lightning,” “Orange

Sunshine,” and “Purple Monterey.”

LSD, according to scientist Dr. Albert

Hofman, who first created it more or less by accident, is not an easy thing to

make, and requires considerable chemistry chops, which Mr. Stanley cultivated

to the point where the term “Owsley” now appears in the venerable Oxford English

Dictionary as a synonym for extremely pure and potent LSD.

Between 1965 and 1967, Owsley was reputed to

have manufactured and sold about 500 grams, or roughly five million hits of

LSD. He became known as “the first LSD millionaire,” or “the Acid King.”

Owsley acid fueled the Beatles’ Magical

Mystery Tour (John Lennon would accept no other); energized the travels of

author Ken Kesey’s “Merry Pranksters” as celebrated in Tom Wolfe’s The

Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (in which Owsley himself appears in a featured

role); influenced Steve Jobs and other computer pioneers to “think different;”

powered the inventive musical juggernaut that was the Grateful Dead, and played

a large part in initiating the wild burst of psychedelic creativity that

characterized the San Francisco Bay Area at that time.

To some users, LSD was a sacrament; to others

a tool of self-discovery or a glorious recreation. To some it was a scourge;

occasionally a literal dead end. (This was reportedly much rarer with Owsley’s

product; other manufacturers often were not so well intentioned, and

adulterated their LSD with chemicals that were cheaper but more volatile in

their effect).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Si-jQeWSDKc

(1950s Housewife Takes LSD in a Controlled Experiment/8:45) Gerald Heard

But, as with acid trips and rocket ships,

what goes up must come down. Owsley managed to elude the long arm of the law

(perhaps helped by the fact that he was camera-shy and surprisingly

nondescript-looking) until 1967, when he was arrested, tried, and sentenced to

three years in federal prison.

Out on bail, he was in the midst of a lengthy

appeals process when he and most members of the Grateful Dead were busted in

New Orleans on December 31st, 1970 (see the lyrics to “Truckin”). Mr. Stanley spent

the next few years in prison, where he applied himself to becoming an expert in

metalworking and jewelry-making.

When he emerged in 1972, Owsley seemed to

have lost his groove. He made no more LSD, rejoined the Dead but squabbled with

them over various issues, experimented briefly and unsuccessfully with

manufacturing another hallucinogen, STP, and went on tour and did sound work

for a number of other bands.

|

| An

Owsley tribute from 2017. LSD was often sold as tiny squares of

blotting paper soaked in the drug. The paper could then be chewed to

achieve the desired effect. The distinctive skull-and-lightning corner motif was designed by Bob Thomas, leader of a group called the Golden Toad, as a mark to identify all of the Grateful Dead's sound equipment. |

By 1982, he was spending a lot of time in

Australia (he thought it would be the best place to be during climate change),

supporting himself and his growing family on an outback farm by raising

cannabis and selling his pricey handmade “wearable art” jewelry on band tours.

He became an Australian citizen in 1996, was diagnosed with cancer, and died in

a car accident in, 2011, survived by his wife Sheilah, four children, eight

grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

It was sometime before that 1970 bust that a

number of San Francisco bands that had made the big time decided to hold a

benefit for a storied and beloved commune/production company called The Family

Dog, which seemed to be perennially strapped for cash.

The Dog were a truly hippie bunch; led by a

long-haired laid-back impresario named Chet helms, they played a huge early

role in introducing and supporting San Francisco’s bands, poster artists,

light-show creators, etc.

|

| The Family Dog. Chet Helms is in the flowered shirt in front of the tree to the left. |

In their earliest days, they had no fixed

venue for concerts, but in 1969 The Family Dog On The Great Highway opened in a

former amusement-park ballroom, just a stoned throw from the Pacific Ocean

across Highway 1.

On the night of the benefit, which I attended

with a Rolling Stone co-worker, the place was packed, wall-to-wall tie-dye,

love beads, and grooving longhairs, there to support the Dog and celebrate the

Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Jefferson Airplane and other proponents of

the San Francisco Sound.

|

The Family Dog on the Great Highway. This photo was taken by Robert Altman in 1969, during one of the then-popular "Monday Night Classes" with iconic teacher-philanthropist Stephen Gaskin.

|

It was beyond hot, the air thick with a

miasma of sweat, patchouli and pot smoke. By the first intermission, my friend

and I were extremely thirsty. There were long lines for the concession stands,

water fountains and bathrooms, so we decided to play the rock-journalist card

to get backstage.

The lights there were dim and patchy, the

close quarters full of people milling around as the next band set up. “Is there

anything to drink back here?" I asked a passing musician. He gestured to a

table in a dark corner with what appeared to be a punchbowl arrangement set up

on it.

As we approached, an indistinct figure

greeted us, offering us two paper cups filled with liquid. I gulped mine down

gratefully, recognizing the childhood taste of cherry Kool-Aid™. As I lowered

my cup, the music started up again onstage, and a splash of green light briefly

illuminated a set of undistinguished features, grinning impishly.

“Have a nice trip,” said this apparition

sweetly, vanishing into the smoke-filled dimness.

“Who was that?” I asked my companion.

“That” he said, with a hint of resignation,

“was Owsley.”

“Wait,” I said, tasting my Kool-Aid

moustache. “Did he really say ‘Have a nice trip?’”

“Uh-huh.”

Fortunately, since we had just been dosed

with Owsley’s finest, we went elsewhere and did.

But that’s another story.

################

20. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Mammy

Morgan’s Hill, Pennsylvania; 1944-1970s.

JUST DOWN THE LANE

About the time that I entered the

world in late 1944, the 19th-century farmhouse at the end of our bumpy

dirt lane changed hands. By the time I was able to toddle down there on my own,

the run-down place was well on its way to being beautifully restored, the tumbledown

barn rebuilt, the grounds planted with new trees and flowerbeds.

The new owners called it “GanAiden,”

Hebrew for “Garden of Eden.” It and they were to broaden my baby horizons

considerably.

|

| GanAiden from our front porch after a storm. |

Ann and Meyer Meyerson were two

hard-working Philadelphians (he was a pharmacist; she ran her own kosher frozen

foods company) who had bought the farmhouse-plus-80-acres as a weekend getaway.

Their only daughter was away at college, and grandchildren were years in the

future. I was of the perfect age and temperament to be doted on.

|

| Me

(on the left) with Myo and sister Susan. The barn in the background was

opposite our house and blew down in a hurricane a few years later. |

They were both small people, a bit

over 5’, Russian-born (in 1904 and 1906), warm, witty, gregarious, urbane yet

down-to-earth, stylish, and to me, exotic. For one thing, they were city

people; for another, they were Jewish (I would not knowingly meet another

Jewish person that wasn’t related to them until I entered high school).

|

| A

surreal masked photo of my sixth Halloween/birthday party. Myo and Ann look

tall only because they're standing on the porch behind us. |

On Saturday afternoons, Myo (I

pronounced his name this way as a tot, and it stuck) would don a yarmulke and

read from a book with unusual black letters. If I asked what he was reading, he

would translate a passage for me.

“Did you understand that?” he’d ask. “No,”

I’d say. “Don’t worry,” he’d reply, “I’m still trying to figure it out myself.”

I once asked Ann if they went to church. She just smiled, looked around, and

said: “This is our church.”

|

On top of Hexenkopf Crag c. 1952: Myo, sister Susan, the Myersons' nephew Richard, Ann, me, my mother, brother David.

|

WWII had ended only recently, but

they never spoke of it, nor of the Holocaust. It was only years later that I

realized that a sensitive and beautifully rendered original pencil sketch that

hung in their hallway, depicting an elderly man wearing what looked like

pajamas, had actually been drawn by Albert Speer, Adolf Hitler’s Minister of

Munitions, during a visit to a concentration camp.

From an early age, I had a standing

invitation to drop on down the lane for brunch on Saturdays, and to visit on

Sundays for “Four O’ Clock Tea.” Ann and Myo talked to me as if I were an

adult, always seeming interested in my opinions and observations.

They liked to discuss art, ideas,

history (they belonged to societies celebrating Abraham Lincoln and Benjamin

Franklin), as well as what I was reading and my adventures in the woods and

fields. They gave me books, ranging from Edward Lear’s nonsense verse to the

drolleries of Ogden Nash to Henner's Lydia, Marguerite De Angeli's beautifully illustrated story

about life as an Amish girl.

I have warm memories of sitting in

their sunny kitchen, chattering away, reading the lavish comics section of the

Sunday Philadelphia Inquirer (my parents got the boring gray New York Times),

and being introduced to foods unlike any I’d previously tasted—bagels with

unsalted whipped butter, cheese and cherry blintzes, stuffed grape leaves,

artichokes, knishes, lattkes, and borscht with sour cream. (The only things I

dug my heels in about were lox and gefilte fish.)

|

| Susan (left), Myo and me at the Philadelphia Zoo. |

Ann was a gourmet cook, and it was

reflected in the quality products of her company, Aunt Leah’s Frozen Foods. On

one of our family’s occasional trips to Philadelphia to visit the Myersons, we

went to the big airy brick-lined kitchen where the kosher delicacies were

prepared in large copper-bottomed pans and huge ovens by friendly ladies in

housedresses, hairnets and aprons.

Ann wrote a little jingle to the

tune of “Little Buttercup” for play on Philly radio stations: “We’ve blintzes

and knishes/And borscht that’s delicious/We’ve kasha with bowties, too/Why

stand by the fire/And work and perspire?/Aunt Leah will do it for you!”

(Bowties are noodles shaped like that accessory.)

|

| Resting after a tour of Independence Hall: Myo, Ann, me, my mother Barbara, Susan. |

As we all grew older, our friendship

continued to flourish. When I was about ten, Ann and Myo acquired a bijou

collection of farm animals—some chickens, a ram and several ewes (insuring baby

lambs every spring), a pair of geese named Sears & Roebuck, and three ducks

known collectively as Hart, Schafner & Marx.

In the 1970s, beginning to feel

their age, they reluctantly sold their beloved GanAiden, but continued their

weekend visits in a lovely little cottage my dad crafted for them out of the

former stables on our property. I was out in the world by that time, but our

friendship continued on my visits home.

|

| The

little cottage my dad built for Ann and Myo out of our former stable.

The silo contained a spiral staircase leading from the bottom bed/bath

area to the second-floor kitchen/living room/bath. It was built into a

hillside, so the second floor opened up onto a patio and lawn. The stone

foundation dates to the 19th century. |

Myo passed away in Philadelphia in

the late 1970s. Ann moved to a retirement community, and when I would visit her

there, we’d go on expeditions to the Philadelphia Art Museum or to local

galleries, where she would remark sagely on the artwork displayed (although one

time, as we admired an exquisite kitchen-based Dutch still life, she reverted

to her foodie self and commented: “You know, they got a bad deal on that ham”).

The last time I saw her, she was as

sharp as ever, reveling in what the retirement-home manager had said to her

when she made a suggestion to improve the efficiency of their kitchens. “He

just looked at me,” she related, with her wonderful deep laugh, “and said ‘To

hell with Mars, Mrs. Myerson, there’s intelligent life in Philadelphia!’”

Indeed.

It wasn’t until I was an adult that

I realized how unusual (and wonderful) it was for a small child to have grownup

friends that were not parents, relatives, teachers or authority figures, to be

welcomed by them without reservation; to be listened to seriously; to be

encouraged to question and think and appreciate ideas and the beauty of art and

nature; and to get to read the funnies while noshing on a bagel.

And all of this just down the lane.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

End of Part Six: More to Come

ALL MY BLOGS TO DATE

MEMOIRS (This is not as daunting as it looks.

Each section contains 20 short essays, ranging in length from a few paragraphs

to a few pages. Great bathroom reading.

They’re not in sequential order, so one can start

anywhere.)

NOTE: If you prefer to read these on paper, you

can highlight/copy/paste into a Word doc and print them out, (preferably

two-sided or on the unused side of standard-sized paper).

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part

One

https://amiehillthrowbackthursdays.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part

Two

https://ahilltbt2.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part

Three

https://amiehilltbt3.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Four

https://tbt4amie-hill.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Five

https://ami-ehiltbt-5.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part

Six

https://am-iehilltbt6.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part

Seven

https://a-miehilltbt7.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part

Eight

https://a-miehilltbt8.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part

Nine

https://amiehilltbt9.blogspot.com/

*********************************

ILLUSTRATED ADVENTURES IN VERSE

NEW! FLYING TIME; OR, THE WINGS

OF KAYLIN SUE

(2020)

https://amiehillflyingtime.blogspot.com/

(38 lines, 17 illustrations)

TRE & THE ELECTRO-OMNIVOROUS GOO

(2018)

http://the-electroomnivorousgoo.blogspot.com/2018/05/an-adventure-in-verse.html

(160 lines, 26 illustrations)

DRACO& CAMERON

(2017)

http://dracoandcameron.blogspot.com/ (36

lines, 18 illustrations)

CHRISTINA SUSANNA

(1984/2017)

https://christinasusanna.blogspot.com/ (168

lines, 18 illustrations)

OBSCURELY ALPHABETICAL & D IS FOR DYLAN

(2017) (1985)

https://obscurelyalphabetical.blogspot.com/ (41

lines, 8 illustrations)

**************************************

ARTWORK

AMIE HILL: CALLIGRAPHY & DRAWINGS

https://amiehillcalligraphy.blogspot.com/

AMIE HILL: COLLAGES 1https://amiehillcollages1.blogspot.com/

***********************************

LIBERA HISTORICAL TIMELINE (2007-PRESENT)

For Part One (introduction to Libera and to the

Timeline, extensive overview & 1981-2007), please go to: http://liberatimeline.blogspot.com/